The Bishop's Palace

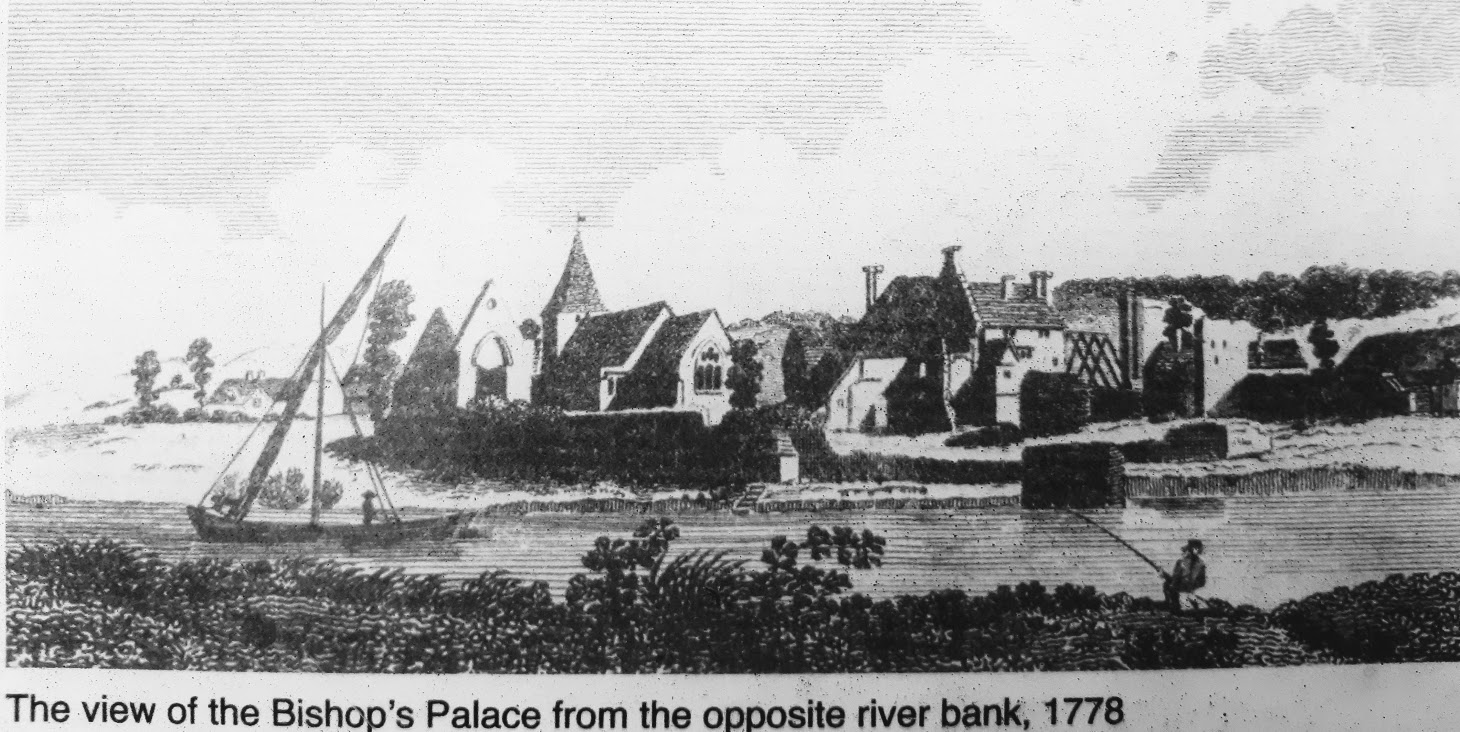

In 1077 Gundulf was consecrated Bishop of Rochester. That's just eleven years after William the Conqueror and his Norman army had invaded England and fought the Battle of Hastings in 1066. Gundulf was a great architect responsible for Rochester Cathedral, the White Tower of the Tower of London, and St. Leonard's Tower in West Malling. Gundulf built for himself a palace by the river at Halling and this was to be a residence of the Bishops of Rochester over the next three centuries.

In 1184, Richard, Archbishop of Canterbury, possibly the second most powerful person in the land, and the man who had succeeded Thomas Becket who had been murdered in Canterbury Cathedral, died in the Bishop's Palace and common rumour was that he was poisoned.

In the folowing 1185, Gilbert de Glanville became Bishop of Rochester and carried out many repairs to the palace. He was followed by Bishop Benedict de Sanctum but within a year King John was laying siege to Rochester Castle and it is unlikely that Halling would have escaped involvement. By 1316 the Palace was falling into decay and the roof had fallen in. Repairs had to await Bishop Haymo of Hythe in 1319 and took a full seven years of restoration. A new Great Hall took over two years to build and cost £120, a staggering amount some 650 years ago. Haymo sheltered at the Bishops Palace from the great plague that ravished the population in 1348-9, including decimating the nearby parish of Dode across the North Downs to the west.

Probably the last bishop to use Halling Palace was John Fisher but unfortunately he ended his days with execution in London by order of Henry VIII. After this it seems that Halling palace became too expensive to maintain and the buildings were allowed to decay.

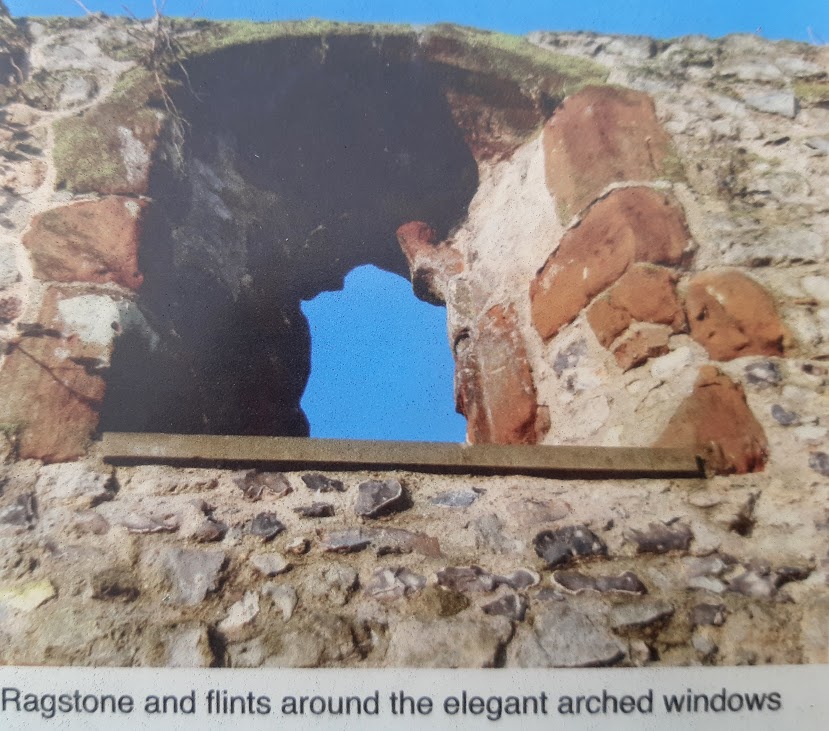

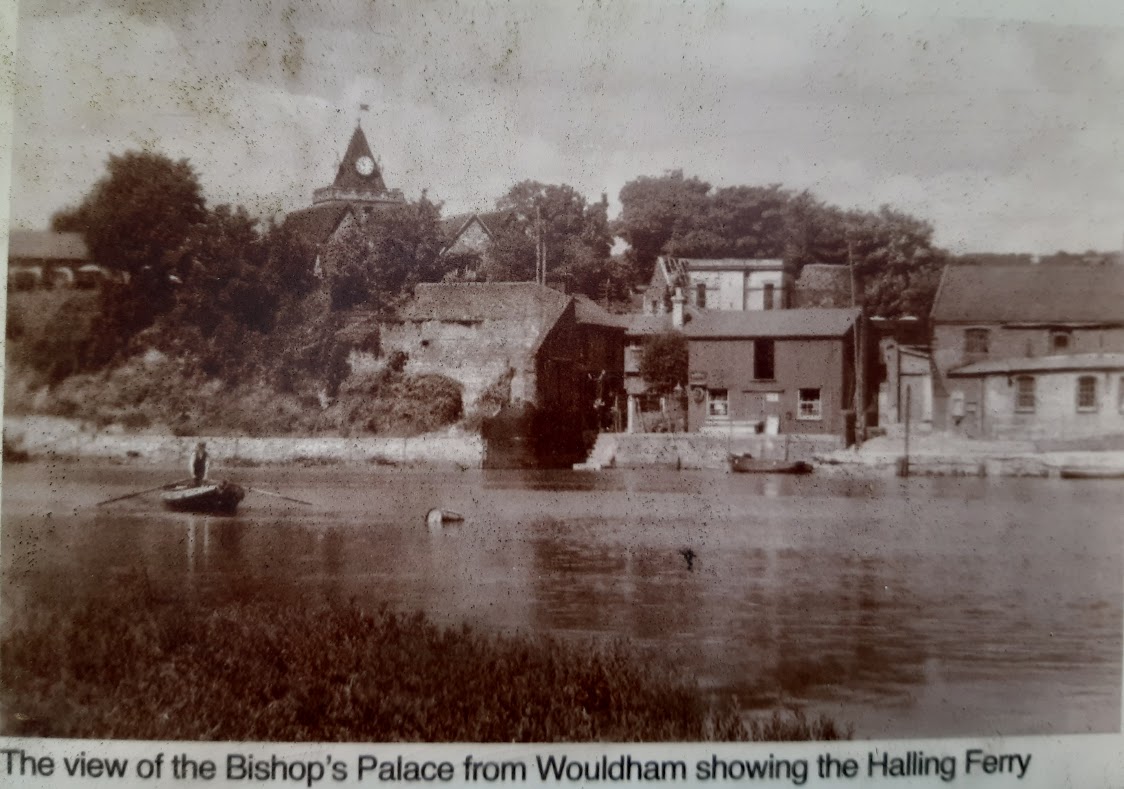

A storm of 1720 blew parts of the hall to the ground. Nearly 600 years after being first built Halling Palace was to suffer the ignominy of becoming a workhouse in 1749 for the villagers of Birling, Luddesdon, Snodland and Halling. Then in 1870 the growth of the cement industry locally and the burgeoning development of the Halling Manor Lime and Cement Works around it led to the last parts of the building being demolished apart from the the west wall of the Great Hall which can be seen still today - now a protected scheduled national monument.

Information from:

'Across the Low Meadow - A history of Halling in Kent', by Edward Gowers and Derek Church, 1979, Christine Swift Bookshop.